Retelling my father's story through photocaptions* |

|

Ray (Renato) Manfredi was born in the Bronx on 25 April 1917, the last of 7 sons of Fortunata Moraca (Baucina, Palermo, Sicilia, 1881‑1979) and dott. Camillo Manfredi (Conflenti, Catanzaro, Calabria, 1877‑1937). Four of Ray's brothers lived to adulthood: Philip (Filippo Lindoro 1904‑1982) alias "Doctor M", an obstetrician who built Longwood Hospital from the former Vincent Memorial, Boston; Joseph (Giuseppe Giovanni 1908‑1983) a family doctor in the Bronx, then in Yonkers; Daniel (Dante Enrico 1910‑1995) a surgeon in Manhattan and the Bronx, and sports physician for Columbia University and the Forest Hills tennis tournament in Queens; and Fred (Federico Romolo 1913‑1977) an attorney in the Bronx who served as trial counsel at the Nuremberg War Crimes Commission in 1946 and contested a Bronx judgeship circa 1950. Fortunata was a professional seamstress whose handwork paid for several ocean passages between Italy and North America. She married Camillo soon after his pharmacy degree (Napoli, 1903). For five years they made a brave start in her mafia‑ridden village on the Palermitan fringe, before she convinced him to migrate to New York—together with their first three sons, Fortunata's elder sister Rosina ("Zizi" 1875‑1965) and Rosina's own two boys. Camillo opened a pharmacy on Manhattan's Lower East Side near Mulberry Street before moving uptown to 245 East 110th Street in Harlem.

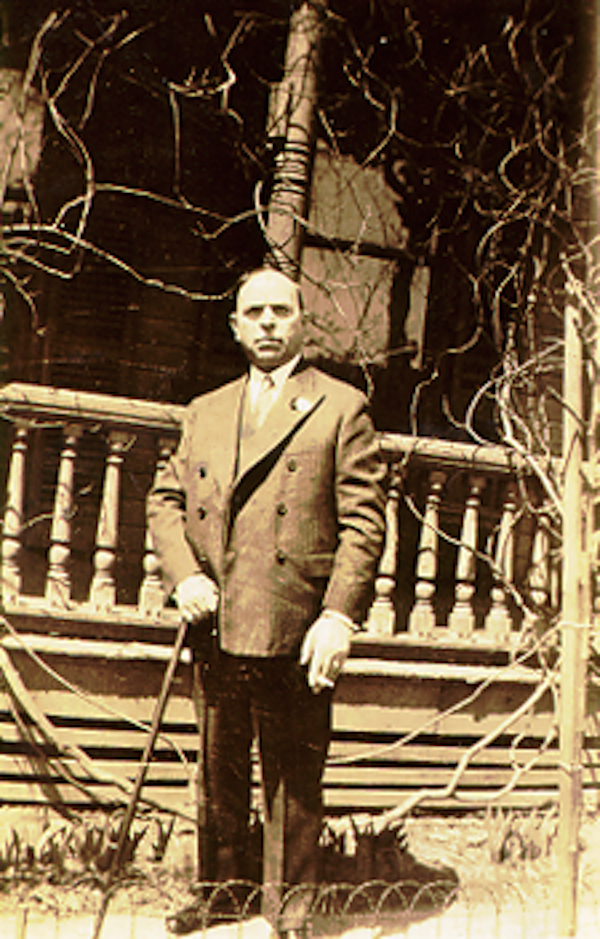

Becoming U.S. citizens in 1911, Fortunata and Camillo moved across the Harlem River to 276 East 153rd Street in the Bronx—where Renato was born—then bought a one‑family house con giardinetto at 3109 Park Avenue @ 158th. This modest woodframe structure was much enlarged in the imaginations of letter‑reading Sicilian relatives, as it initially accommodated 12 people in addition to Camillo's pharmacy. In the late 1960's it succumbed to cyclic forces of real‑estate finance (alias "the Bronx is burning" syndrome) unleashed by Robert Moses' Cross Bronx Expressway. The generous fig tree in the yard was transplanted, but did not withstand the shock.

Throughout his life, Ray supported his brothers' activities and was supported by them in turn—all according to Fortunata's master plan. He recalled childhood survival strategies like selling scorecards and pencils informally in Yankee Stadium, or printing i numeri (unofficial lottery tickets) in the basement of 3109. Such early (ad)ventures set an enduring pattern of mutual aid. The family climbed up in the relatively egalitarian U.S. interlude between WW2 and the triumph of the neoliberal oligarchs.

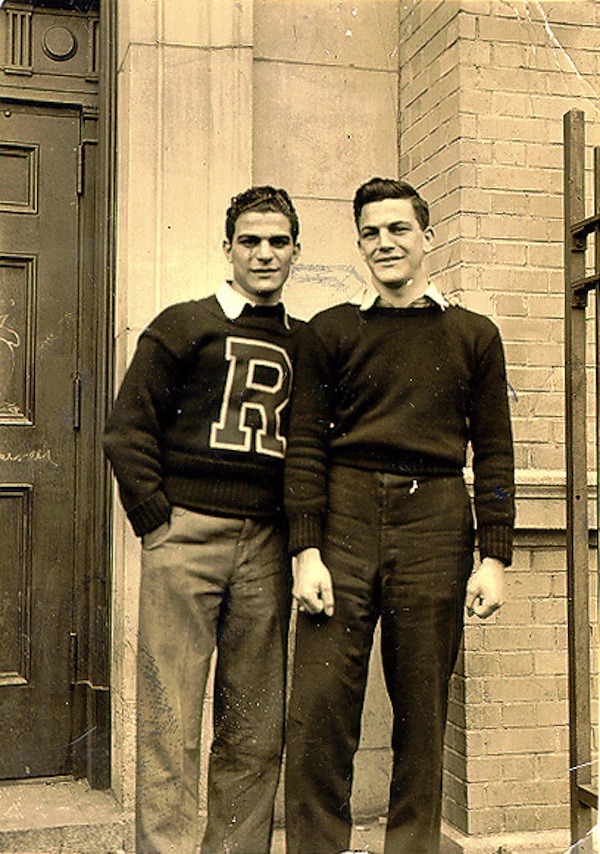

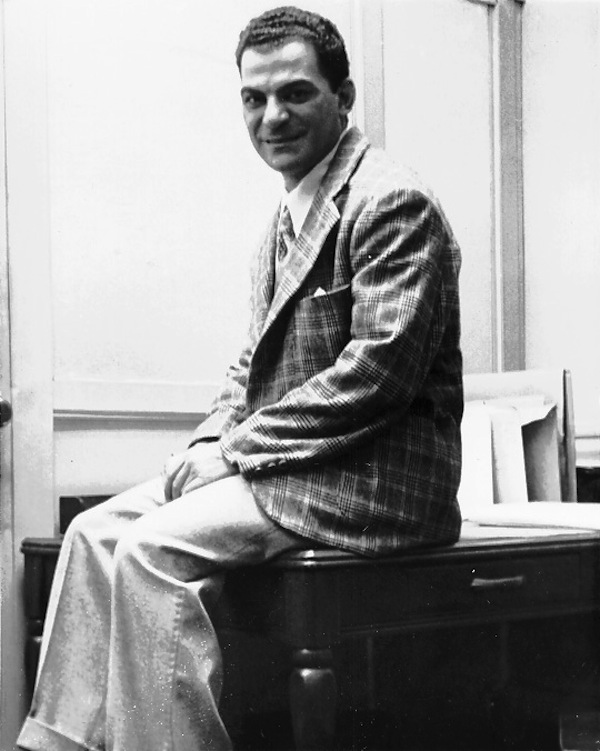

Ray (stereotypically misnamed as "Tony" in a press caption) excelled in North American football and wore the varsity "R" of Teddy Roosevelt High School on Fordham Road, before enjoying three scholarship years (1936-39) at Brown. His Ivy League degree fell through along with his career as a collegiate halfback, but in 1943 he completed an LL.B at the Brooklyn campus of St. John's University.

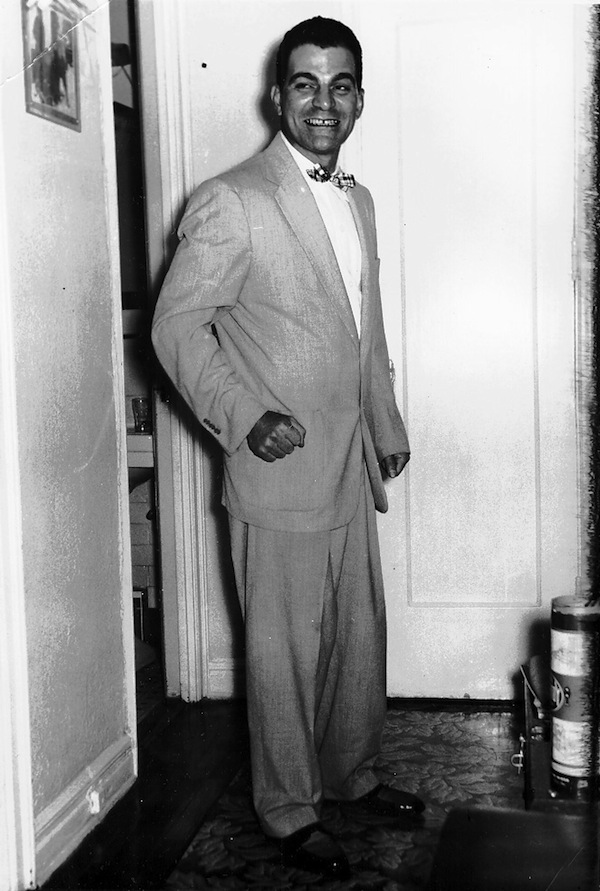

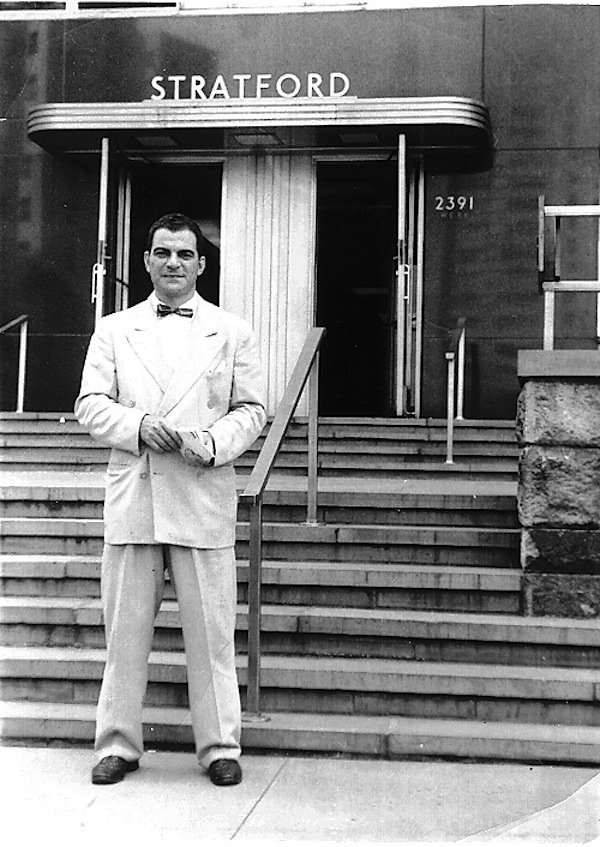

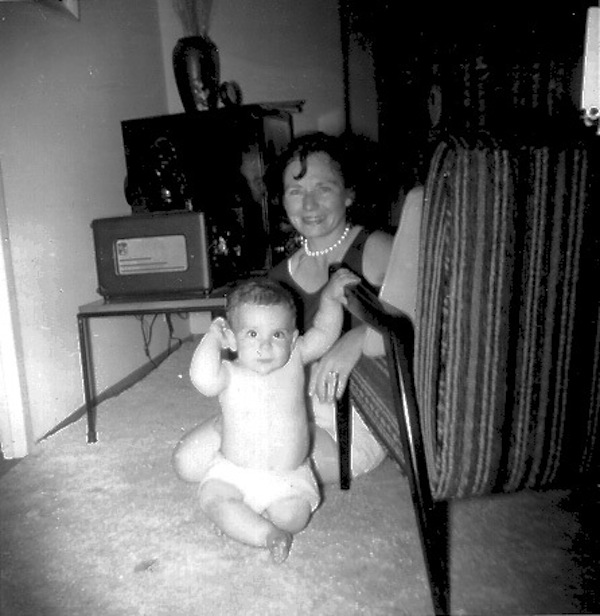

In 1953, when Ray married Mary Elizabeth Hegarty (Boston, 1916‑2004), Fortunata allocated them a double bed at 3109, but insubordinately they found their own apartment thirty blocks north in Fordham Hill—a campus of nine blond modernist slabs set in the leafy former grounds of the Webb Institute of Naval Architecture. There I was born in 1956. As fallout from suburbanization and the first (1970's) neoliberal debt crisis, the property's profitability declined to the point that it was sold off to its occupants in 1982 in the "largest… tenant‑sponsored coop conversion… ever undertaken in the city". By then Ray and Mary were qualified by age to continue renting at submarket rates, and stayed put on the third floor of 2391 Webb Avenue for the rest of their lives.

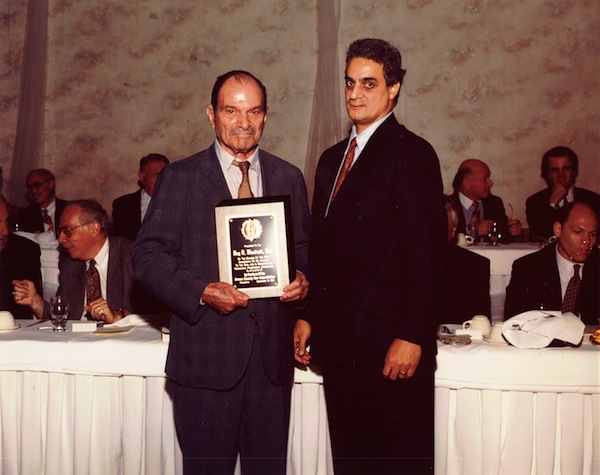

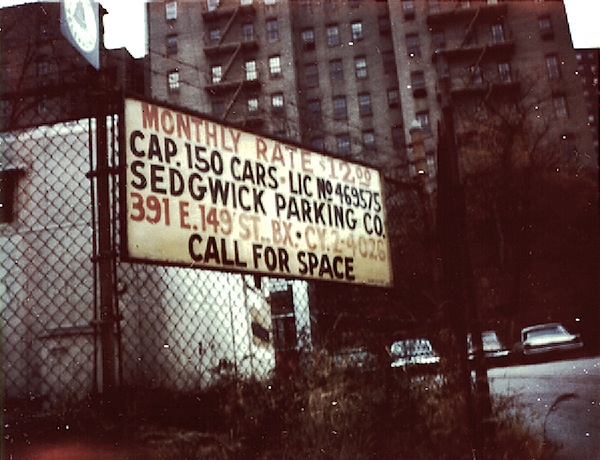

Until Fred moved from Undercliff Avenue to City Island, he and Ray shared an office in "the Hub" at 391 East 149th Street by the Third Avenue elevated tracks. In 1956 Ray won an underdog criminal defense case in the city's charged context of race and class, only to lose the fee when the acquitted client fled the country, so he turned to the more dependable income of mundane civil law. After Fred's death, Ray sublet workspace at 2455 Sedgwick Avenue, two flights up from the traffic court and directly across the street from Fordham Hill. He retired in 1996 after 50 years as a member of Bronx County Bar Association.

In 1936 Camillo developed cancer and chose to repatriate himself while still able, so his NY family waved goodbye from a Manhattan pierside and he died in Santu Mangu (San Mango d'Aquino, Catanzaro, Calabria) the following year, in the ancient house of his half‑brothers Filippo and Tomasso. In 2004, Ray and his cousin Orazio, an olive oil producer, organized the carving of Camillo's name on the family sepulcher, where Ray's own physical remains are now also entombed.

After Camillo's departure in the midst of the Great Depression, Fortunata and Rosina sustained their families on both sides of the ocean while closely managing the five brothers' economic and personal affairs. In the postwar Keynesian boom, Fortunata's kulak drive and Phil's entrepreneurial charisma led the collective into various land investments. A parking lot on Sedgwick Avenue at 175th Street, sold in 1970, became the footprint for the Mitchell‑Lama nonprofit housing project at 1520 Sedgwick ("the home of D.J. Kool Herc… [and] the birthplace of Hip‑Hop"). On many afterschool afternoons in the mid '60's, my father and I ran 200‑meter laps between the rows of cars. More conventionally picturesque, a lakeside hilltop near the New Jersey and Pennsylvania lines, bought from the estate of a German‑American brewer, failed in its originally intended use as a paying baseball camp, but functioned for six decades as the Manfredis' utopian retreat—a veritable commune (minus hippies, of course). To accommodate Phil's annual birthday bash, a 20‑meter dining hall was added with assistance from the four Annicelli brothers—well‑seasoned journeymen of the New York building trades, who came up with the Manfredis in the same Morris Avenue neighborhood. In September 1953, Mary celebrated her honeymoon hoisting pails of mortar onto a chimney scaffold for Red (Ralph) Annicelli, the stogie‑smoking brickmason of the (not‑always‑harmonious but unfailingly loyal) Annicelli quartet.

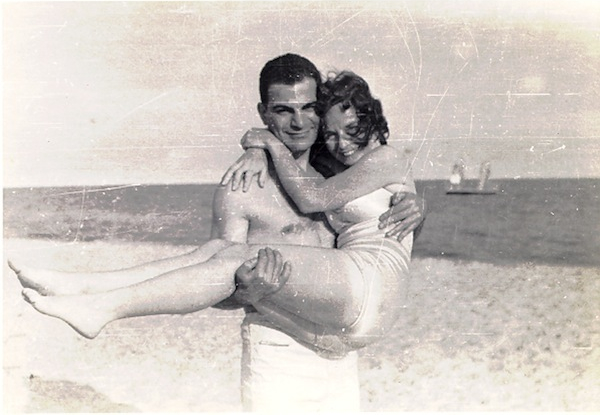

Construction help for Phil also figured in how Ray and Mary met. After escaping an ill‑advised religious vocation, Mary did "dielectric and radome research for radar antennas" in MIT's Rad Lab. (After the war, the radioactive heat of Building 20—where Mary had helped conduct experiments on the 'hot' side of a lead screen—was metaphorically recycled, in the barrack's creatively ramshackle space, to "incubate" [.pdf] Chomskyan linguistics and other new information sciences.) In the late '40's she resumed her main interest of biochemistry, first in the idyllic coastal setting of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, then in the pathology lab of Boston's tech‑heavy Lahey Clinic. On Saturdays she also covered the lab at Phil Manfredi's much smaller hospital, which is where she was first "eyed" (their word) from the top of a ladder by Ray who was dutifully painting the ceiling of his brother's building at the time. By way of introduction, Ray contrived to drip paint on Mary's overcoat—a perfect opportunity to apologise and clean it off face‑to‑face. Their cross‑cultural relationship grew in idealism from facing down reciprocal ethnic prejudice—not to mention the uncomfortable novelty of Mary being the sole straniera of all the Manfredi spouses and the only one with postgrad education.

After Dan died in 1995, Ray carried his brothers' legacy alone, and with rapidly failing health after Mary's passing in 2004. According to my mother's wish, I escorted my father to Sammangu and Palermo in 2004, and again in 2007, so that he could know his respectively paternal and maternal cousins. In between those trips, we received reciprocal visits in New York and imported quantities of olive oil produced by Orazio's son Filippo.

In April 2007, New York State Motor Vehicles automatically renewed Ray's license for 10 years—until his 100th birthday, no questions asked—but it was obvious that neither he nor his car belonged on the road anymore, and in December 2007 a woodsmoke inhalation accident finally pushed him to sell the mountain property and share out the proceeds as his brothers had agreed. The site's own natural vitality had diminished apace with his—the Romantically pristine 'frontier' atmosphere of the '50's having yielded to the interstate era's toxic exurban sprawl, and the natural environment further threatened by unregulated hydro‑fracking gas wells.

By the end of 2010, Ray's horizons had shrunk to the three corners of Fordham Hill, Arthur Avenue (the Bronx's Italoamerican food zone) and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital (where Medicare got him four years' worth of intensive treatment for deafness, dementia and heart disease). In April 2012 after two monthlong bouts of hospitalization and rehab, he had lost the ability to stand and struggled even to eat. Insistently he would ask the caregivers when and how his life would end, finding scant reason to remain without dignity or enjoyment—apart from a few choice and unexpected moments. On April 18th, rolling out of Allen Hospital in a wheelchair and entering the shadow of the Broadway elevated train, he spontaneously exclaimed "Hotdog from a pushcart!" The afternoon was suitably warm and an Egyptian‑staffed Sabrett fry‑truck franchise was parked a few blocks away, on the Bronx side of 225th. Two dollars and two minutes later, my father had already wolfed the whole cylindrical, halal confection plus hot sauce, impishly calling for a beer to wash it down—forgetting that New York sidewalks are less free today than they were in his 20's. Then on May 6th, Ray's last full day of life, we sat in sunshine by the Hudson watching clouds blow by and he said "Stay here forever". So ended 95 years of enthusiasm for simple pleasures won by cooperative effort in the abundance of the New Deal and eked out with frugality in tougher times. Recounting these experiences as we ran out his concluding lap together, my dad remarked that having seen "America" at its best, he was happy to return to the ancestral home which his father Camillo refused to leave permanently behind.  |

|

the location of this page is http://manfredi.mayfirst.org/raccontoPatronimico.html

last updated 1 May 2014 return to home page |